Supply Chain Reaction

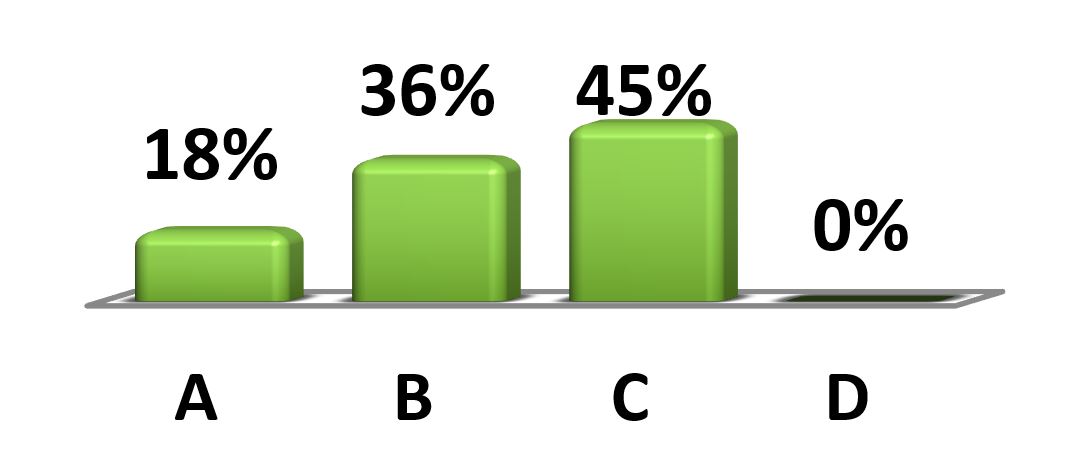

This week I was invited (wearing my corporate hat) to speak at an event run by Global Insight Conferences, focused on the food and drink supply chain. My contribution was the only part of the day addressing sustainability and the brief was to address ‘strategies to drive sustainability in supply chains’. The event featured live feedback from delegates provided by OMBEA represented by the very helpful Mitt Nathwani, who kindly collected the voting results for me which made it much easier for me to discuss them here. The facility worked quickly and seamlessly and added a great extra dimension to the event. I used the system first to reprise the sense of work I’ve talked about in previous posts (see the ‘Farms, Forks & In Between’ post), around what people understand by the word ‘sustainability’. With limited time, I used a cut-down version, asking the audience to choose one preferred definition from environmental protection, social development, economic success and long-term resilience. The environment came out as the overwhelming favourite which set the scene rather neatly for a discussion around the UN Sustainable Development Goals as a framework for defining what sustainable organisations look like. I also asked which group in society has the most responsibility for delivery sustainability and, contrary to past responses, private individuals were the most favoured whereas that group is usually in third place (see the ‘Blue Planet Blues’ post) of the choices (A-government, B-business, C-individuals and D-civil society), the results of which are shown in an OMBEA chart below.

Regular readers of this blog will know that the SDGs represent a highly robust framework around which to develop a sustainability strategy (see the ‘Owned Goals’ post) and I used them as a key part of the presentation structure but also included a number of pieces of work on what consumers look for from businesses and how corporations respond (or not). Encouragingly, half of the audience reported some or significant knowledge of the Goals, which is a higher proportion than might normally be expected, with only one in six completely unfamiliar with them. Of course, this group was not representative of the public at large, or even necessarily people within the food industry, as they had elected to attend a conference discussing “efficient, collaborative, innovative” supply chains, but it is still reason for hope that the SDGs are becoming more mainstream.

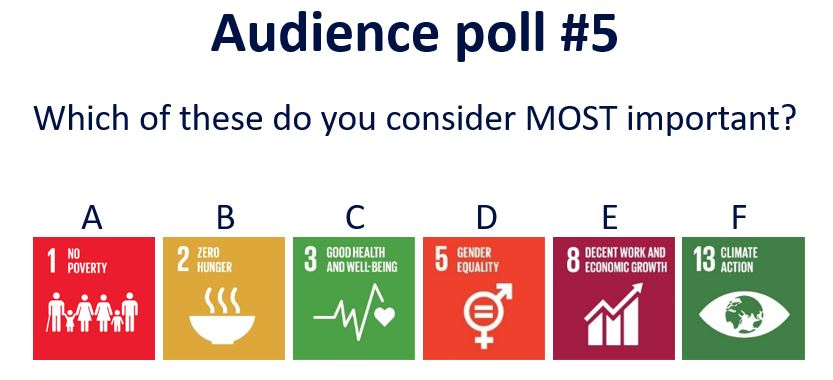

Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC) published some work last year comparing UK corporate and citizen priorities within the SDGs and what follows is (my rather than their) speculation on the findings. Business priorities were found to be Gender Equality (SDG 5), Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8) and Climate Action (SDG 13). With gender pay gap reporting high on the corporate agenda over the past 12 months, that might explain the presence of SDG 5 when past work by Globescan has found the European ‘top 3’ to be Climate Action, Quality Education (SDG 4) and Responsible Consumption & Production (SDG 12). Citizen priorities were Zero Hunger (SDG 2), Good Health and Wellbeing (SDG 3) and No Poverty (SDG 1), which ae clearly miles apart from the corporate priorities; indeed SDG 1 was in the bottom three business priorities. This citizen ranking may well be related to the widespread publicity received in 2017 by food banks and the social issues they are there to address, but this is again speculation on my part.

I used the six Goals noted above for part of the audience feedback through Ombea, asking delegates to pick the one they considered the most important and the one they considered the least important. This was before they saw the PwC work so there was no ‘leading the witness’. The responses cut across PwC’s findings, with Climate Action and Good Health & Wellbeing coming joint top closely followed by Zero Hunger. Much more surprisingly, at 45% the clear leader as ‘least important’ was Gender Equality followed some distance behind by Decent Work and Economic Growth. The gender balance in the group was around 2:1 in favour of men, which may or may not be relevant; I would prefer to think that the responses represent the UK’s legal landscape in which gender equality is protected by law (highly imperfect though this turns out to be in practice) and therefore some of the other issues might seem to have greater urgency. More positively, at another event where I spoke later in the week (the N8 Agri-Food Annual Conference in Liverpool, of which there will be more in a future post) the overall speaker faculty managed 45% representation by women, a tidy coincidence with the figure noted above. Not quite parity, but close.

So, what does this tell us? Firstly, and most importantly, it illustrates the fact that there can be no simple answers because there is no consensus on the priorities. Surveys routinely show variation in priorities (as expressed by ranking of the SDGs) across geographies and industry sectors, but even in a single room containing people who might be expected to be broadly similar in experience and outlook, given why they were there, the differences are significant and notable. Beware the purveyor of the ‘silver bullet’; systems problems are rarely susceptible to simple solutions. Secondly, it shows that the concept of sustainability is still closely linked to environmental concerns. As an environmentalist as well as a sustainability professional, I’m not entirely unhappy to see that, but it clearly isn’t the full picture. With more time, I would have liked to explore this with the group further, especially given that the priorities highlighted by PwC’s research were primarily social (it is worth pointing out that other work, by KPMG for example, showed different priorities again). Thirdly, and very positively, it shows that there is an appetite to address the issues, even if there is no one simple way of doing it.