Blog

In the Bleak Midwinter

Another year has turned and, as the festive song “Home for the Holidays” has it, it feels like nothing’s changed. Atmospheric CO2 continues to rise, the Amazon rainforest continues to be felled, and vulnerable people around the world continue to be abused by warmongers and tyrants. Many people I know working in Sustainability are seeing reduced resources and commitment, with a focus on reporting compliance which is one of the perverse outcomes of the attempts to do good through driving transparency in companies’ activities. All this at a time when the impacts of climate change are becoming progressively more obvious, but the media (with some honourable exceptions) seem collectively intent on burying the bad news. Anyone who has been watching the sci-fi drama series Silo (based on a series of books launched in 2011) cannot have failed to see the irony. The diversion runs deep, with LinkedIn recently hosting a staggering quantity of hot air around the relative merits of real and artificial Christmas trees. Setting aside the inevitable virtue signalling from some of the contributors, everyone seemed to be missing the point that the tree almost certainly isn’t the real issue. The boxes of ephemera wrapped in plastic piled up beneath them, the miles travelled as people visit family, the wasted food, the additional consumption of chocolate driving deforestation and biodiversity loss, and so on it goes.

Actually, I haven’t seen a study comparing the relative impacts all those things, so I am just making an educated guess, but I doubt that the trees will turn out to be the worst impact. Also, interestingly, although I didn’t have the energy or inclination to read the whole thing, I didn’t notice anyone offering many options beyond artificial or natural. No tree at all is an option, and one that would have a zero footprint, or alternative decorations using cuttings rather than a whole tree. A potted natural tree returned to the garden at the end of the holiday period was mentioned by at least one of the contributors, and one that could be carbon negative if done well. Western traditions are not the only contributors to this consumption, other parts of the world have their own and perhaps those in midwinter may share an ancient common root in celebrating the passage of the shortest day. We don’t need to worry about whether the sun will return any more, as we now have science to explain astronomical phenomena, so maybe we can dial down the over-consumption. In fact, and deeply ironic given the impact of that over-consumption on climate change, not being warm enough is becoming progressively less of an issue.

So far, so bad. But I’m not Scrooge (at the beginning of the story, of course) or the Grinch, so there is something positive to add here too. The good news is that we don’t need actions from governments or corporations in this arena, we can take action for ourselves, and we can do it right away (or at least for the next consumer binge in our part of the world). Gifts that don’t contain more unnecessary stuff (the capacity of the UK self-storage sector has tripled in less than 20 years), no immediately disposable items like plastic wrapping paper, catering that considers leftovers (not just the infamous turkey curry) and the impact of supply chains for things we barely notice that we are consuming. After all, by and large, we manage without individually wrapped tiny chocolate bars for the rest of the year. Such products were the subject of another thread on LinkedIn following a suggestion to Mondelez about allergen listing which was met with an unbelievable level of smug patronising. Some shortage of Christmas spirit as well as humility there, it seemed. All that said, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that every unbought gift means that someone in a factory in a low-income country may be losing some of what little they earn. Sorry – a bit of bah humbug at the end after all.

Yet More Hot Air

And so the much-trumpeted COP26 is over, delegates jetting back home having failed yet again to deliver the wholesale change which humanity and all of the other species on the planet so desperately need. The reported statistic that the largest ‘delegation’ at the event comprised lobbyists for the fossil fuel sector perhaps tells us all we need to know about what didn’t happen. Even the rhetoric from the supposedly progressive nations of the West was undermined by an unholy alliance in which major polluters seek to continue on their current path so as not to economically disadvantage their citizens (or at least the elites) and developed economies (the US and Europe) seek to limit the bill for the impacts of their early industrialisation. Whatever we end up with as the global temperature rise above pre-industrial levels, the rise we’ve seen so far, itself perilously close to 1.5oC, is a consequence primarily of the activities of a small number of nations and most significantly benefited a very small proportion of the inhabitants of even those. According to a recent report published by the Institute for European Environmental Policy, Oxfam and the Stockholm Environmental Institute, taking into account the then current pledges from the world’s nations, the difference in environmental impact per person based on their individual wealth is stark. The world’s top 10% (which equates to an income from around double the UK median, so hardly the preserve of Tech Billionaire playboys) have emissions at nine times the level consistent with limiting the rise to 1.5oC, with the poorest 50% well below the target carbon threshold. This most recent failure to deliver real change on emissions echoes the disappointment of past meetings all too faithfully. I would have used the title COP Out for this post, except that I had already used it after COP24 similarly failed to get to grips with the burning elephant in the room.

The tears nearly shed by Alok Sharma, COP26 President, at the close of the conference seem to have been the genuine response of a man frustrated by the limited progress of the event, rather than those of a politician concerned about his reputation. Contrast that with the Prime Minister travelling to and from Glasgow on a private jet to see the contradictions within the world of politics. Of course, emissions from an individual flight between London and Glasgow are not material even in the context of the travel of thousands of delegates and lobbyists to attend the conference, let alone in the broader impact of industrialised nations day-to-day, but it illustrates that the actions taken by politicians are contingent and they usually have an eye on their key stakeholders as much as does any commercial enterprise. The ‘disappointment’ expressed by the Prime Minister that COP26 didn’t deliver what it could have done and needed to do might yet lead to a political re-organisation which puts climate change more explicitly back into the brief of a government department. If so, then perhaps Mr Sharma will get a second chance to make good change for the UK and influence other nations. So, if COP26 wasn’t a success (billed as it was as our “last, best chance” of limiting global heating to 1.5oC and so avoiding the worst of the unfolding climate catastrophe), was it a complete failure? The answer is no, of course. The can has, once again, been kicked down the road as vested interests, corporate and political, ensure that they mitigate the economic impact on their own activities. Some positive signs of change have emerged, though, but much weaker, slower and later than needed, and the tensions between developed and emerging economies have a long way still to play out.

And what of us as private citizens? It is one-dimensional to blame the impacts of consumerism on businesses which promote consumption and absolve individuals of any responsibility for their actions. At the very least we can choose to boycott organisations with the most egregious environmental and social misconduct and use our own voices to press for change economically and politically. As I type this, I am in an hotel near London about to start a course on principles and requirements for validation and verification (of environmental impacts), which is part of the means by which organisations can be held to account. Having travelled here in my fully electric car, I was forced to re-charge it in the car park of a nearby supermarket (well done Lidl) as the hotel offers no EV charging facilities. The receptionist was unaware of why this is the case, and it seems that I am far from the first person to ask. Whilst eating breakfast, the background (actually at a quite unavoidable decibel level) radio bombarded guests with seemingly endless adverts for Black Friday Deals. Leaving aside the commercial realities of such ‘deals’, they are yet another reminder of the normalised nature of consumption in the lives of the wealthy few across the planet, and a clear aspiration for those in less privileged circumstances. In polls, the overwhelming majority of UK consumers agree with targeting net-zero by 2050 or earlier, but the basis on which this is to be achieved is rarely made clear. Driving less, eating less red meat and some other modest lifestyle changes are accepted, but the reality will be far more demanding in terms of change. On top of that, there will be unintended consequences of changes to the global economic system, and we need to keep focus on a just transition for all. A global win will require local sacrifices, and those who have the most (us in the developed West and wealthy elites around the world) will be the ones who need to make the most sacrifice.

Ring in the New

It is probably too far into January to wish readers a Happy new Year, but this week’s change at the top of the American governmental system promises the start of something happier for social equity within the USA and the global environment. Joe Biden’s accession speech referenced the racial inequality in America and the existential risk of the climate crisis and America re-entering the Paris Climate Accord as a result of one of his first executive acts is very welcome news. The presence of a woman as Vice-President would be remarkable enough in itself, but Kamala Harris’s mixed heritage makes her truly exceptional within the nearly 100 Presidents and Vice-Presidents of the past two-and-a-quarter centuries. Biden’s speech also acknowledged the considerable difficulties which his administration will face, first in properly addressing the Covid-19 pandemic and secondly in navigating the deep political differences which will make his social and environmental agendas hard to achieve. Nevertheless, for now at least there is cause for optimism.

Contrast that with the mixed signals on this side of the Atlantic from recent government actions. Despite a manifesto pledge to end plastic waste exports (and the fact that 85% of citizens polled in 2019 were in favour of the UK doing so) there are fears that this may yet happen as EU law has not been transposed. On top of that, the UK Government is also facing accusations of failing to uphold environmental, social and animal welfare standards in its approach to agri-food imports. An amendment proposed in the House of Lords was rejected by a Commons vote and the Government’s position seems to amount to little more than “we won’t do it, so we don’t need to legislate – trust us”, which rather begs the question, if they’re really not going to do it, what’s stopping them from legislating? On top of that there are more mixed signals, this time on carbon. The fact that the previous Busines Secretary, Alok Sharma, left his post to focus full-time on the delayed COP26 looked like a possible sign of a government taking the climate crisis seriously. Since then, despite government funding of £8m (a much smaller number than it sounds, in this context) for a net-zero industrial cluster, it has chosen not to intervene in plans for a new coal mine in Cumbria. Sharma’s replacement, Kwasi Kwarteng, couldn’t avoid the hypocrisy, but played it down to an extraordinary extent by saying “There is a slight tension between the decision to open the mine and our avowed intention to take coal off the gas grid”. Slight tension? On the positive side, the Defra minister has stated that embedded carbon in imports could be included in future emissions targets (notwithstanding that the UK is set to miss the next two carbon budgets). Let’s hope these words prove to be more reliable.

Where the Government has some way to go if it is to match rhetoric with action, at least some businesses are doing a better job of reflecting the urgency of the climate and pollution crises and the public’s desire to see improvements. The issue of plastics has slipped down the priority list during the pandemic, but it will certainly come back. Tennents and Heinz both removing plastic packaging from cans, Beefeater is removing plastics from bottles and Tesco has announced that it has removed 1 billion pieces of plastic packaging. On the carbon front, Leon is introducing carbon-neutral burgers and fries. More broadly, Garnier is introducing digital sustainability labelling and Apple is linking executive pay to performance on ESG targets. Perhaps the Government should take note…

Table Steaks

As we draw towards the end of a difficult year, the promise of a vaccine-driven easing of the impact of the pandemic has been overshadowed by the emergence of a new strain (well, three months old in fact) of coronavirus and increased travel restrictions over the holiday period. The environmental impact of the local versions of lockdowns around the globe is still to be fully evaluated as restrictions continue to come and go, but the Global Carbon Project estimates the worldwide impact to be a drop of 7% across the year. Although this is of an unprecedented scale, it brings into stark focus what will be needed to achieve net zero by 2050. The UK’s sixth carbon budget, delayed like so many other things by the pandemic, has now been published and calls for 78% decarbonisation by 2035, partly as a consequence of slow progress so far. That is broadly equivalent to two-thirds of the pandemic effect cumulatively every year for a decade and a half. Set against the last year, that is almost unimaginable, and certainly unachievable without root and branch change to the system as a whole. In the food sector, land use change through afforestation (including 10% of farmland) and hedgerow planting coupled with major dietary change continue to be the key policy proposals. The CCC wisely includes the term “low-cost, low-regret” to describe the necessary actions, as ‘losers’ from the changes will need to be supported through a transition to the new-look system. The recommendation is a 20% shift away from all meat by 2030 rising to 35% by 2050, and a 20% shift from dairy products by 2030. In a study published by Survation in September 2019, nearly two-thirds of respondents said they would be prepared to eat less red meat with nearly one-third prepared to become vegetarian as part of the move to net-zero.

That was then, and this is now. A study published in The Grocer this week (their annual Top Products Survey) found a range of changes in UK food shopping habits through the pandemic. As I write mostly about food systems, I’ll skip quickly over the drop in sales of personal care products (including toothbrushes and deodorant) and move on to meat. Sales of steak apparently increased by 8.7%; demand for chicken and sausages also rose. The emissions impact of meat varies from species to species and across types of husbandry, and the published data doesn’t include an analysis of country of origin. Also absent is an analysis of reductions in consumption elsewhere in the food system; out of home businesses spent much of the spring with their doors closed so lost sales from QSR establishments such as McDonald’s and Burger King, typically sellers of high volumes of beef products, would offset some of the rise in retail consumption. Other factors may be at play too. The springtime combination of good weather and additional free time for many people may have contributed to more consumption of some types of meat in back-garden barbecues (sausages were another category where a retail rise was reported). Households not impacted by job losses and furloughing would have been saving money otherwise spent on commuting and daily cups of high-street coffee and may simply have spent some of that on trading up in the grocery basket – a trend also seen when households save money by reducing food waste. A decrease in sales of sugar and chocolate noted in the same analysis may suggest that comfort eating may be less of a factor than might be imagined.

More encouragingly, sales of fresh vegetables, notably tomatoes, also increased so the data may simply reflect an increase in home cooking in place of food prepared out of home (school meals included, of course). In-home cooking, indeed any cooking, matters as part of the overall system. A paper recently published in Nature Food shows that the carbon impact of the ‘use phase’ of food products can account for 50-60% for cooked vegetables. They are still overshadowed in total carbon impact by animal proteins, of course, but should not be ignored in vegetables are to make up an increasing part of our collective diet. This energy usage is a consequence of the method, not just the need to ‘pre-process’ them by cooking. Vegetables will typically be boiled in a pan of water, with a quantity of water several times the weight of the food also being brought to the boil and held at high temperature throughout the cooking process by continued application of energy from the hob. Clearly the type of hob makes as big difference; electric hobs can be powered by renewable energy far more easily than gas. Modern induction hobs match gas for responsiveness and convenience, but that isn’t much help for people who own gas ovens and can’t easily afford a replacement. The study examines cooking methods in some detail and contains some useful content for food businesses looking to address their downstream scope 3 impact. The point of all this is simply to underline the fact that subsets of data in isolation are typically meaningless, and decisions taken without an understanding of the system as a whole are likely to flawed.

Stop Press!

It has been a very long time since my last blog post; the Covid-19 pandemic notwithstanding I’ve been very busy, but mostly with things that are client confidential as getting out and about has been difficult at best and often impossible. Even outside the lockdown periods meetings moved online and non-critical visits to food premises did the same. The new online world has become normal to the extent that pets don’t just wander across the background of Zoom and Teams calls, they are actively introduced. I have ‘met’ a puppy and a kitten in the last couple of weeks although, it must be said, their contributions to the substance of the respective meetings was modest.

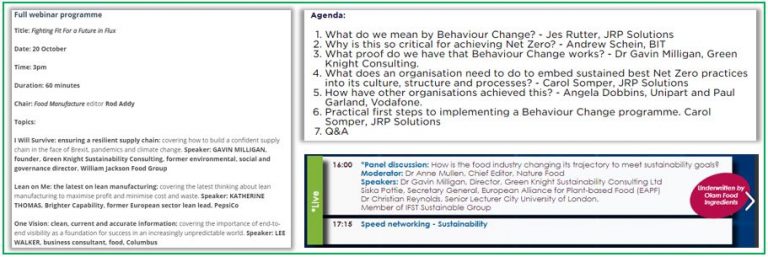

Lord Deben, in contrast, made a significant contribution in his opening remarks to the recent strategy session organised by the Biomass Refinery Network, noting that climate change is a symptom, not a cause. Two-way communication between innovators and policy-makers is vital if the bio-economy is to play an effective role in the net-zero transition that the UK and many other countries are seeking to make by 2050, with many businesses setting targets sooner than that. A recent poll of UK consumers found that almost two-thirds were in favour of bringing the UK’s target forward from 2050. It wasn’t evident whether the respondents were prepared to make significant sacrifices in their own lifestyles but other surveys have suggested that a majority are willing to cut back on if not cut out activities linked to high emissions. Behaviour change will be one of many necessary responses by individuals and within organisations, and I have recently contributed to several online panel discussions on the importance of behaviour change to delivering the net-zero transition how the industry generally is adapting to meet evolving sustainability challenges.

Valorisation of waste streams was the most popular area for discussion in a poll of food sector specialists at another (virtual) meeting I attended recently, with a clear link both to the bio-economy and a broader resource-efficiency strategy, and it remains an area of interest to funders of projects in the UK and beyond. As we move towards the endgame of the UK’s departure from the EU, but nowhere near the end of the changes it will bring, the future differences in direction between UK and EU policy will have been on many people’s minds. The future challenges for the agri-food system and society more broadly are global and what drives citizen’s choices rises above political boundaries. In the UK we are used to thinking of the response to plastics as a local issue, but it impacts countries around the world. China, for example, has announced a crackdown on single-use plastics and there is a move to ban plastic sachets or all but food applications. Sometimes the response seems counter-intuitive, with a move towards plastic rather than away. The carbon impact of transporting glass containers is inevitably more significant than lighter-weight plastic. Over 7 years ago, Marks & Spencer moved its pickle range from glass to plastic with a unit weight saving of up to 85% and something similar is happening as I write to a range of tertiary brand fruit juices in France. Laminated (FSC-certified) board-based packs are being replaced by plastic bottles containing 50% recyclate (see the image below).

For established closed-loop systems, this is perhaps better than incinerating mixed-material packaging, if that is what actually happens. Waste packaging collections in France are routinely of mixed materials, as is also the case with general waste at recycling centres which is highly heterogeneous. It is not evident when material is deposited what will happen to it, but the bottlers of Jafaden juices (sold by E Leclerc supermarkets) are clearly getting their recyclate from somewhere. Sentiment around plastics has moved during the pandemic, with PPE especially leading to significant new waste streams. The kick that lockdowns have given to home delivery has also meant that the transport emissions profile as well as waste packaging has not benefited as much as might have been expected from such radical societal change. Net zero will entail far more change than we have seen through 2020, and we have a long way to go even to hit existing carbon budgets in the UK, let alone anything more stretching. It is welcome then, that the Prince of Wales’ Corporate Leaders Group has written to the Prime Minister urging an interim target to accompany net zero by 2050. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC), Chaired of course by Lord Deben, is due to release the UK’s next carbon budget before the end of the year, and policy currently lags behind the necessary reductions in emissions here and elsewhere in the world despite the attention the topic is apparently receiving in legislatures. As the annual boom in consumption that accompanies seasonal festivities is nearly upon us, we should all think twice about what we put on our Christmas lists.

Oil’s Not Well

The recent news that atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are continuing to rise is a sobering reminder of the fact that the rhetoric associated with action on the global climate emergency is not being matched with meaningful action. The press release from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) covers not just carbon dioxide, but also methane and nitrous oxide. The cumulative effect, total radiative forcing, has increased by 43% in less than three decades. This year’s conference of the parties COP25, hosted in Madrid, followed on from COP24 in merely kicking the can down the road for yet another year rather than prompting the far more robust responses which are necessary. The Paris COP21 meeting in 2015 gave rise to a range of commitments around the world which are yet, if the WMO statistics are any guide, to translate into sufficient action to have anything like enough positive impact. A small crumb of comfort may be found in other news in the same week that this year looks set to see the largest fall in electricity production from coal on record.

Inevitably, a move away from fossil fuels will impact on the interests of those businesses the profits of which depend on the sector remaining economically viable. The significance of this economic driver is multiplied when fossil fuels are at the heart of a national or regional economy. Texas is perhaps the archetypal example of such places; inspiration for the 80s television programme Dallas, replete with Stetsons, shoulder-pads, wheeler-dealing and casual treachery. It remains a cliché, but one firmly rooted in reality. Travelling across the west of the state is more reminiscent of Mordor than the wide-open spaces of Hollywood Westerns, with enormous vehicles, nodding donkeys, gas flares and trailer parks for the workers as far as the eye can see. But, even here in the home of oil, there are further crumbs of comfort. Large-scale wind farms such as that in Mesquite Creek opened by Mars in 2015, which produces electricity equivalent to the demand of all their 70 US factories (there is a sister installation in the UK), can also be seen across parts of the state and next door in New Mexico is an innovative community of ‘earth ship’ inhabitants. There is also a refreshing degree of honesty about the limitations of the recycling infrastructure which we could learn from. Closer to home, the Netherlands’ highest court has upheld a ruling requiring the government to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25% of 1990 levels by the end of 2020, a target which sadly will be almost impossible to achieve.

Environmental issues seemed to be more prominent in the UK’s recent general election campaign than in recent hustings, and the UK is set to host next year’s COP26 meeting in Glasgow. Hopefully our politicians, whatever the distractions of the UK’s departure from the EU, will take a real lead on the issues to justify the apparent global lead implied by the declaration of a climate emergency earlier in the year and the extension of the national climate ambition to net-zero by 2050. Even motoring journalist and long-standing public climate sceptic Jeremy Clarkson appears also to have conceded that global warming is real, and a cause for genuine concern. But has there been a real shift? Mark Carney, moving on from the Bank of England to a role as United Nations Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, has warned that the world will face irreversible heating unless firms shift their priorities soon. Analysis by a leading pension fund, surely the epitome of an organisation which has to think over the long term, has shown that the cumulative effect of the policies of all companies committed to taking action, they are consistent with warming of nearly 4oC, a level which will be catastrophic for human society and natural ecosystems around the globe. As I type this, Australia is burning.

Tailored Sustainability Support for Resilience and Growth

Contact

Phone: +44(0)7967 025215

Email: contact@greenknight.consulting

More Links

© 2025 Green Knight Sustainability Consulting Ltd